Has The Transfer Portal Killed the March Madness Upset?

In the wake of this weekend's chalky first round, the media class has declared the March Madness upset dead. Is that true?

There will be no Cinderella stories told this year.

Michigan edged past KenPom darling UC San Diego, which was doomed by a slow start and a hostile whistle. Yale couldn’t keep up with Texas A&M on the boards. Grand Canyon was blown out of the water by Maryland, while Utah State met a similar fate against UCLA. High Point looked out of its league against Purdue. McNeese, one of a precious few underdogs to advance to the round of 32, was walloped by the same Boilermakers squad on Saturday morning. Drake ran into JT Toppin and Texas Tech.

This season’s round of 64 was one of the chalkiest in recent history. The highest-seeded mid-major teams still standing are #10 New Mexico and #12 Colorado State, the latter of which was outright favored against its first-round opponent.

The Lobos and the Rams are each roughly seven-point underdogs entering Sunday night. If both were to lose, the remaining field would consist solely of single-digit seeds sans #10 Arkansas.

This fact has been quickly seized upon by our nation’s most reactionary sports critics. Outkick’s Clay Travis confidently tweeted that “NIL has destroyed mid-majors in college basketball because all their talent gets scooped up by big money teams.” In an arbitrarily-capitalized YouTube title, Fox Sports’ Aaron Torres asked: “Have the best players TRANSFERRING - KILLED MARCH MADNESS UPSETS?”

A cursory Twitter search of “NIL” and “March Madness” reveals a similar sentiment common among fans.

Is that true? Are Travis, Torres, and the general public correct?

First of all, the indisputable — the gap between the 2025 tournament’s haves and have-nots is the widest in history. Will Warren of Stats By Will recently wrote a piece analyzing how this year’s field stacks up against fields of the past. Comparing teams using KenPom’s adjusted efficiency margin metric, his findings were stark:

The gap between 1 and 16 seeds is +42.86 AdjEM on average, the highest ever.

The gap between 2 and 15 seeds is +26.84 AdjEM on average, the second-highest ever.

The gap between 3 and 14 seeds is +20.96 AdjEM on average, the highest ever.

Lastly, the gap between 4 and 13 seeds is +16.48 AdjEM on average, which is not the highest ever. Just kidding: it’s the highest ever.

Long story short, the 2025 tournament’s elite teams are “superpowered,” in the words of Warren, while the 2025 tournament’s scrappy underdogs are about as weak as they’ve ever been. Who or what is to blame?

It’s hard to land on anything except NIL and the transfer portal. This season’s historically dominant batch of #1 seeds includes Auburn, which rosters Morehead State’s Johni Broome, Furman’s JP Pegues, and FIU’s Denver Jones, and Florida, which rosters Iona’s Walter Clayton, FAU’s Alijah Martin, Marshall’s Micah Handlogten, Belmont’s Will Richard, and Chattanooga’s Sam Alexis.

Duke has taken a different approach to team-building, using a titanic NIL budget to collect a mountain of blue-chip talent. Houston is unique in its bounty of veteran, home-grown contributors, but even the Cougars’ top two scorers are transfers.

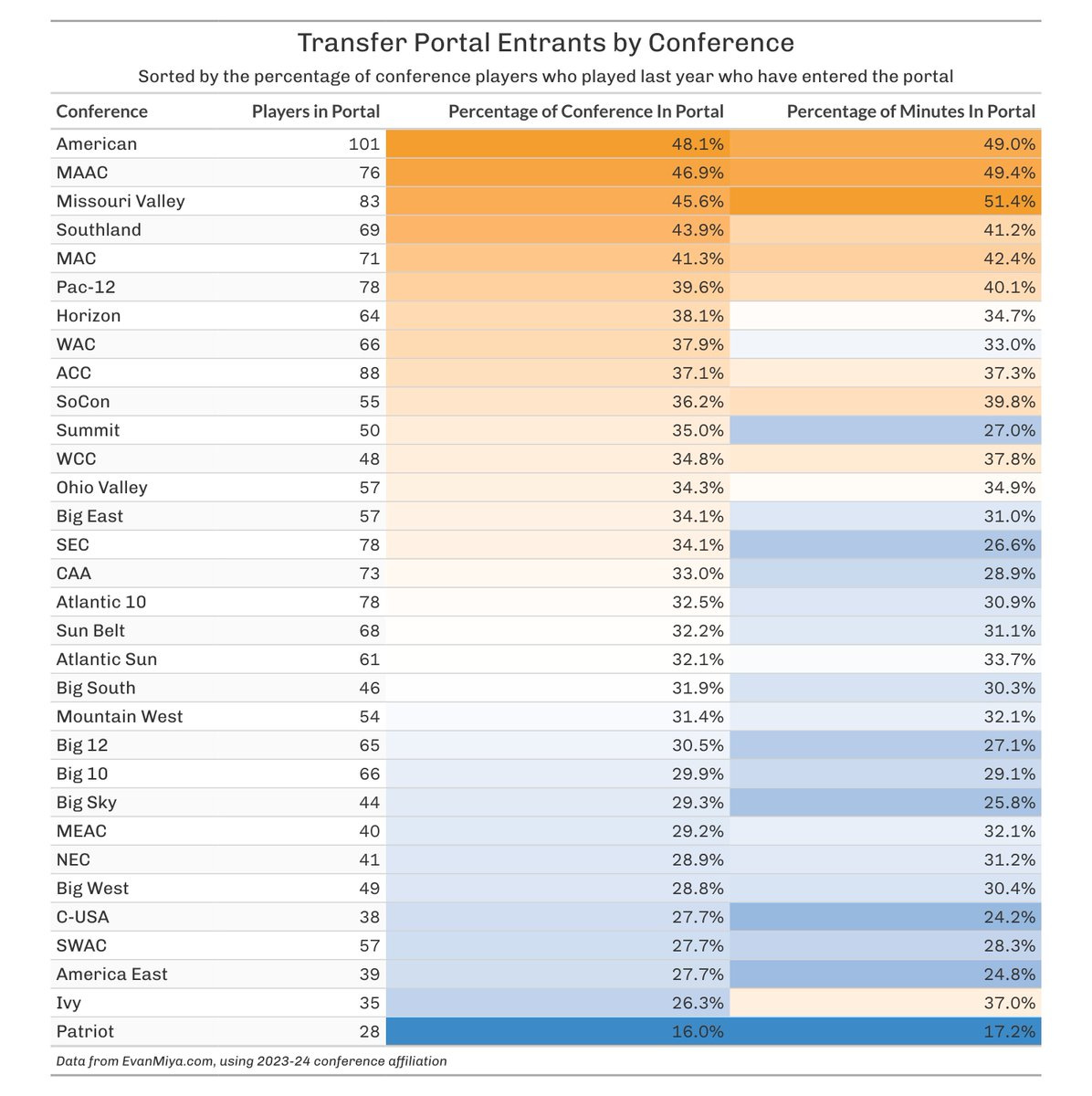

Conversely, the top mid-major leagues suffered a collective down year after being stripped for parts last summer. The Mountain West, Atlantic 10, American, and Missouri Valley all saw significant drops in average AdjEM from 2024 to 2025. The former two had roughly a third of their players from last season transfer, while the latter two had roughly half of their players from last season transfer.

It’s safe to say that yes, this year’s NCAA Tournament field was dramatically imbalanced, and yes, NIL and the transfer portal played a significant role in that disparity. Auburn, Duke, Florida, and Houston (and Tennessee, and Alabama, and Texas Tech…) are among the strongest teams at their seedline in recent memory, while this year’s crop of mid-majors was simply not very deep. Outside of UCSD, McNeese, and Drake, there weren’t many underdogs with profiles that lent themselves to tournament success.

Is this what every year is going to look like? Does this mean the upset is dead?

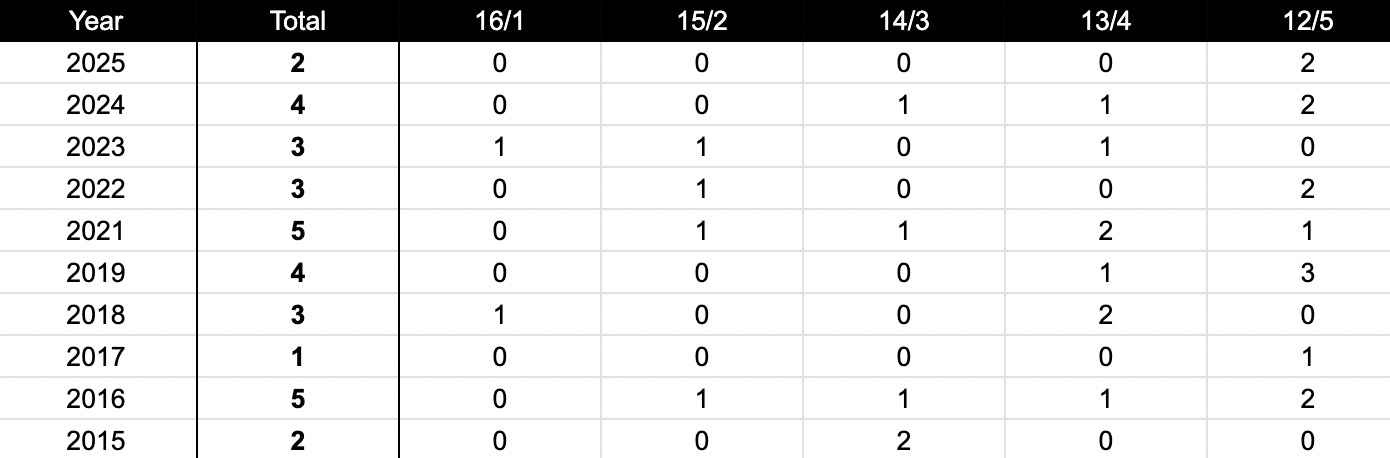

To answer the second question first: of course not. This year’s tournament hasn’t been unprecedentedly chalky; it featured the fewest Round of 64 upsets since 2017, but commentators of the Travis/Torres ilk made similar complaints after that year’s tournament, and after 2015’s, and after 2019’s, and so on.

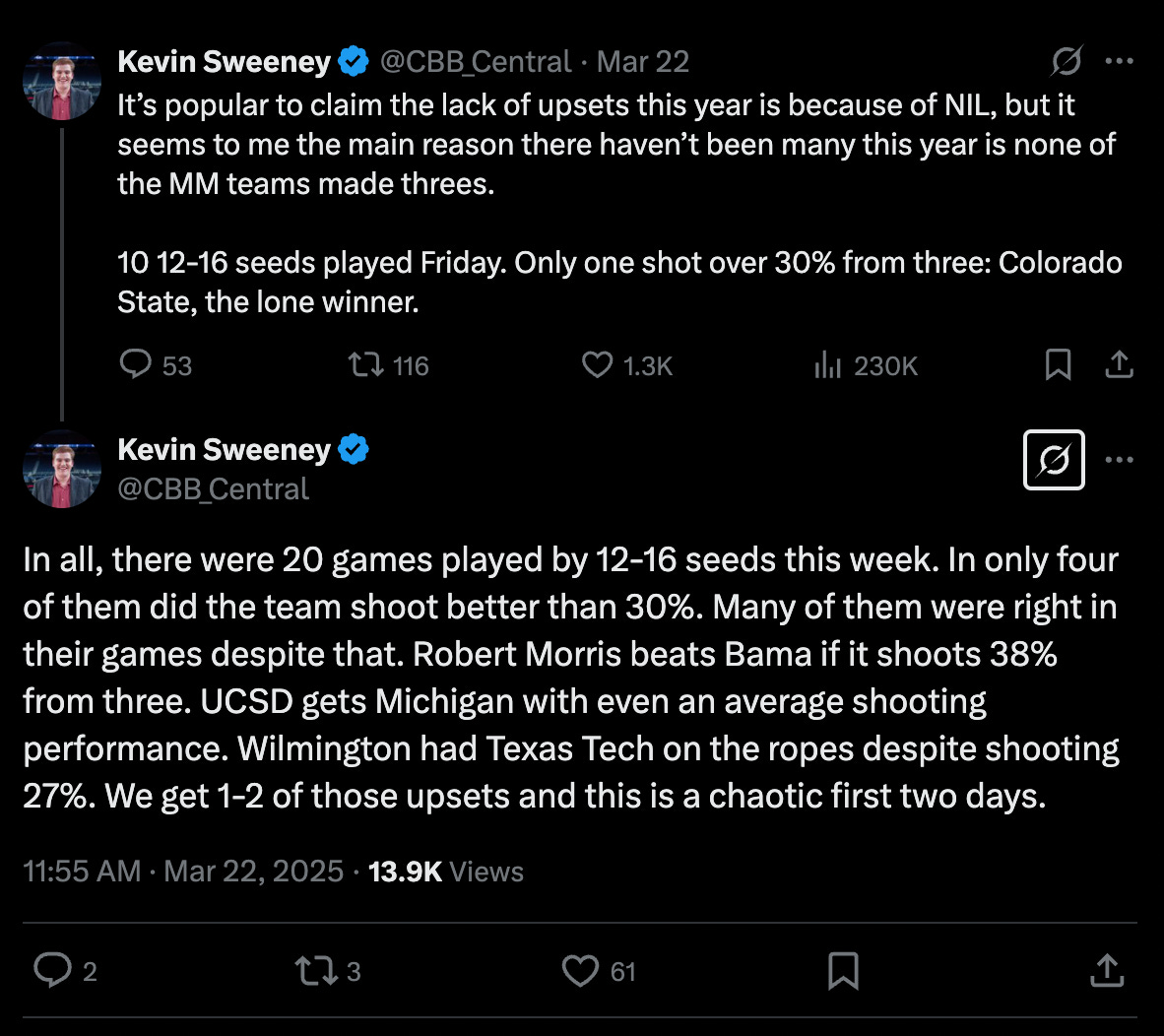

The upset will never be “dead” in a single-elimination tournament that consists of 40-minute games that can be swung by a couple three-pointers in either direction. Take last weekend: as Sports Illustrated’s Kevin Sweeney pointed out, the underdogs simply didn’t see their triples fall during the first round.

Despite going ice-cold from deep, Robert Morris, UCSD, and UNCW hung tight with their opponents. If all three of those teams made a few more shots, Torres would have posted a YouTube video entitled “Is this the GREATEST NCAA TOURNAMENT OF THE DECADE?”

Most of the cold-shooting 12-16 seeds that Sweeney references were capable from beyond the arc; nine of them ranked among the nation’s top-100 three-point shooting teams. However, only three of those nine made 30% or more of their triples during the first round. Instead of an existential crisis about the future of college basketball, could this year’s dearth of upsets be more appropriately attributed to unfavorable variance or the NCAA’s much-discussed overinflated Wilson ball?

The common and histrionic rebuttal to this point is that the athleticism gap between the haves and the have-nots has gotten so great that a team like UCSD, which made 36.1% of its triples on the year, shot 13 percentage points below its season average in its tournament game because it was overwhelmed by the size and length of Michigan.

I do not find this explanation particularly convincing. I will concede that Michigan’s three-point defense is better than that of, for example, Cal State Fullerton; however, the assertion that UCSD simply couldn’t get its shots off against the Wolverines isn’t supported by data. ShotQuality, a metric that takes into account the position of defenders, expected UCSD to score 16 more points against UM than it did based on the shots it took.

This holds true for multiple other underdogs, including Robert Morris. Although it is certainly possible that these teams were affected by the increased athleticism of their competition, they were also severely hampered by bad luck.

The point: yes, there were more bloodbaths than usual (Oregon-Liberty, Arizona-Akron, Maryland-Grand Canyon, Iowa State-Lipscomb, etc.). But even in a year where the gap between the haves and have-nots is the greatest it’s ever been, the tournament’s first round, though very chalky and generally unexciting, was a few favorable rolls away from being memorable. Drawing grand existential conclusions based on a weekend of miserable shooting luck is your prerogative, but I think it’s silly.

Now: will every year’s field look like this?

If someone were to propose the thesis that NIL and the transfer portal have permanently increased the talent differential between power conference teams and mid-major teams, I wouldn’t push back very hard. We are living in an era where the big dogs are as empowered as ever and the small fish are struggling to stay afloat. It could very well be the case that most tournament fields of the near future will be significantly less balanced than the fields we used to know.

However, there are many reasons to think that the 2025 tournament is imbalanced to a degree that won’t be replicated again. For one thing, the sheer number of elite teams included in this season’s field is unprecedented. With an AdjEM of +31.07, current KenPom #5 Tennessee would rank as KenPom’s top team of the 2022-2023 season. For another, the upcoming transfer class will be greatly diminished as college basketball’s COVID-year elders become all but extinct. The portal will never again be as bountiful as it was in years past.

There’s also the looming House settlement, which will rework NIL deals, allow schools to share media-rights revenue with athletes, and force schools with football programs to make potentially difficult decisions surrounding the allocation of money. Any currently relevant analysis of the effect NIL and the portal have had on March Madness will have to be reevaluated over the coming years.

Taking all of the above into consideration — there are major challenges facing mid-major basketball programs, but it is senseless to declare the NCAA tournament upset dead based on two days of play.